Omansyah, a 42-year-old fisherman living on Komodo Island, is deeply concerned about the extent of tourism development in the Komodo National Park.

The latest policy is seeking to compel him and other villagers to move out of their ancestral island for the sake of Komodo dragon conservation, and he believes the change could severely impact his life along with those of other native people.

Omansyah said the establishment of the Komodo National Park Office in 1980 under the New Order regime had created a number of issues for the local people, but now, with tourism expanding, more restrictions and more drastic changes had come.

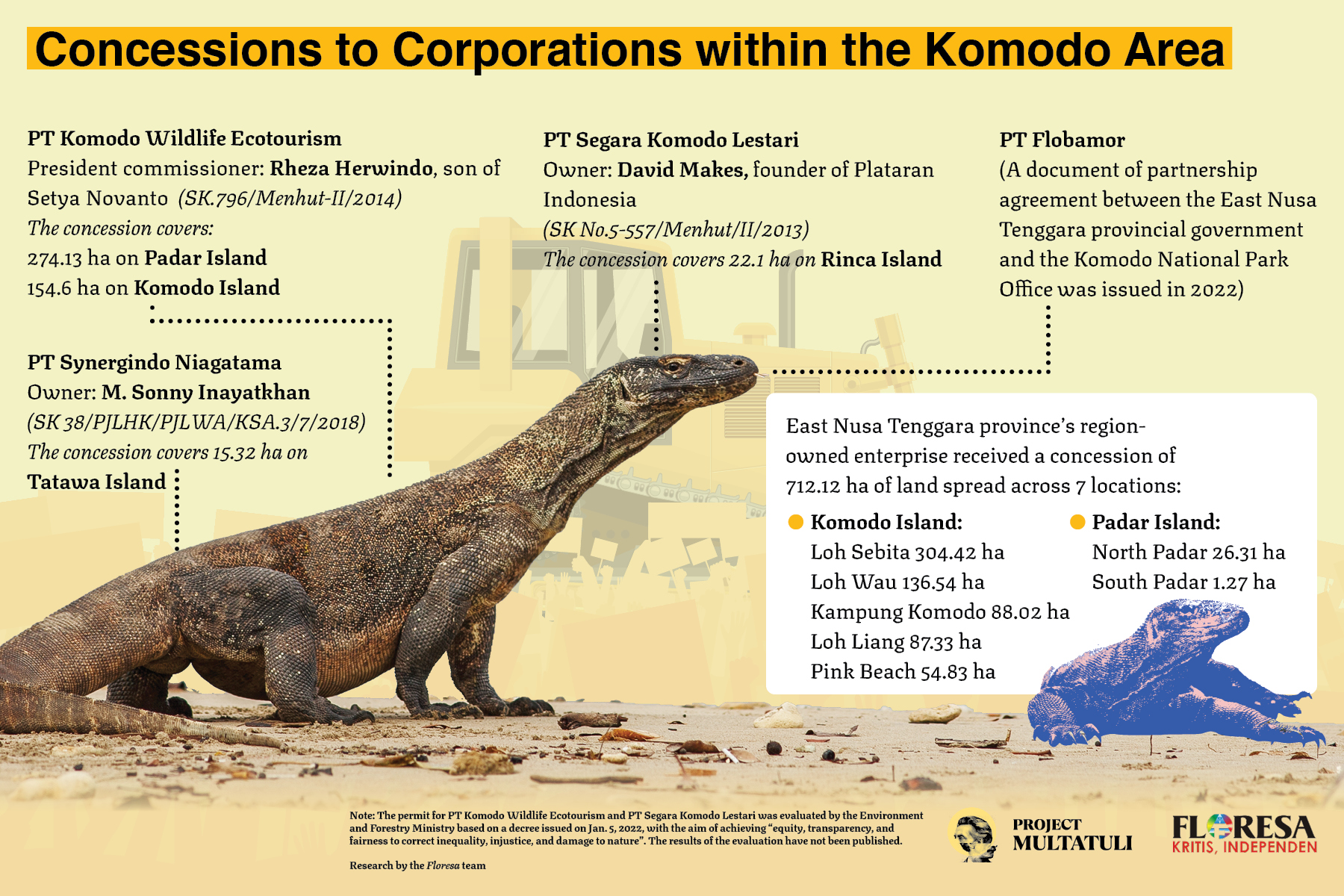

In August 2022, the local government granted PT Flobamor, a corporation based in East Nusa Tenggara (NTT), control of part of Komodo and its surrounding islands. The company’s partnership with the Environment and Forestry Ministry resulted in a concession totaling 712.12 ha on Padar Island and Komodo Island, including 304.42 ha in Loh Sebita and 136.54 ha in Loh Wau.

On top of that, the government closed off two adjacent marine areas that used to serve as local fishing grounds. According to Omansyah, these zones were the backbone of fishing in the area. Changing their function had constrained local people’s incomes.

“We are just little people. If we don’t go to the ocean, we will have nothing,” said the father of five, adding that the new regulation would not stop him from fishing.

“Off Loh Wau and Sebita, fishermen can easily catch fish, squid, and more,” Omansyah continued.

“Fishermen can use trawling nets; the current is not that strong. I once managed to catch two tons of squid in just one night off Loh Wau.

“If [we can’t fish] off Loh Sebita and Loh Wau, how are we going to eat? How are we supposed to source food?” he asked, noting that the day’s catch provided sustenance for the local people.

“One day, the Komodo people may not eat fish anymore and [the label of] ‘fishermen’ may only be symbolic.”

Unwelcome Changes

Komodo village, which lies in Komodo National Park, is home to 500 households with a total of 2,000 people. The people of the area, known as the Ata Modo, have been living on the island for hundreds of years, long before it was turned into a conservation area by the Dutch government in 1915 and a national park by the Indonesian government in 1980.

For generations, the Ata Modo and the island’s Komodo dragons have been living side by side. The Ata Modo believe that Komodo dragons are their siblings, born from the same spiritual mother. In the Komodo language, the dragons are called sebae (twins).

Before the 1980s, most Komodo residents worked as farmers or fishermen. Their territory stretched from what is now Komodo village to Loh Liang and Loh Sebita.

The vast ocean surrounding Komodo Island not only connects the local people to neighboring islands but also functions as a source of food, including fish, octopus, and sea cucumbers.

The livelihoods of the local people changed with the establishment of the Komodo National Park Office in the 1980s.

Access to fishing areas became more limited. Many fishermen put away their nets and became craftsmen. Some villagers also turned to selling souvenirs and food at tourist spots in Loh Liang, a 15-minute boat ride from Komodo Village.

A greater number of fishermen and farmers changed occupation when the government made sweeping zoning changes in 2001. Numerous fishing areas were changed to marine conservation zones and tourism spots for diving and snorkeling. Fishing was prohibited in these areas, and fishing and farming were limited to designated areas called “traditional utilization zones”.

The local people were also forced to relocate from their native village in Loh Liang to what is now Komodo village.

Nur Cahya, a food vendor in Loh Liang, reminisced about the old days of farming in the erstwhile village, where she was born and raised.

“We used to have a lot of coconut [trees], but the National Park Office cut them down,” the 49-year-old woman said.

Waves of Investment

According to the Environment and Forestry Ministry’s zoning map, the people of Komodo village were permitted to use just 27 ha of land in the 2012-2018 period. But the 2001 zoning changes were not the last.

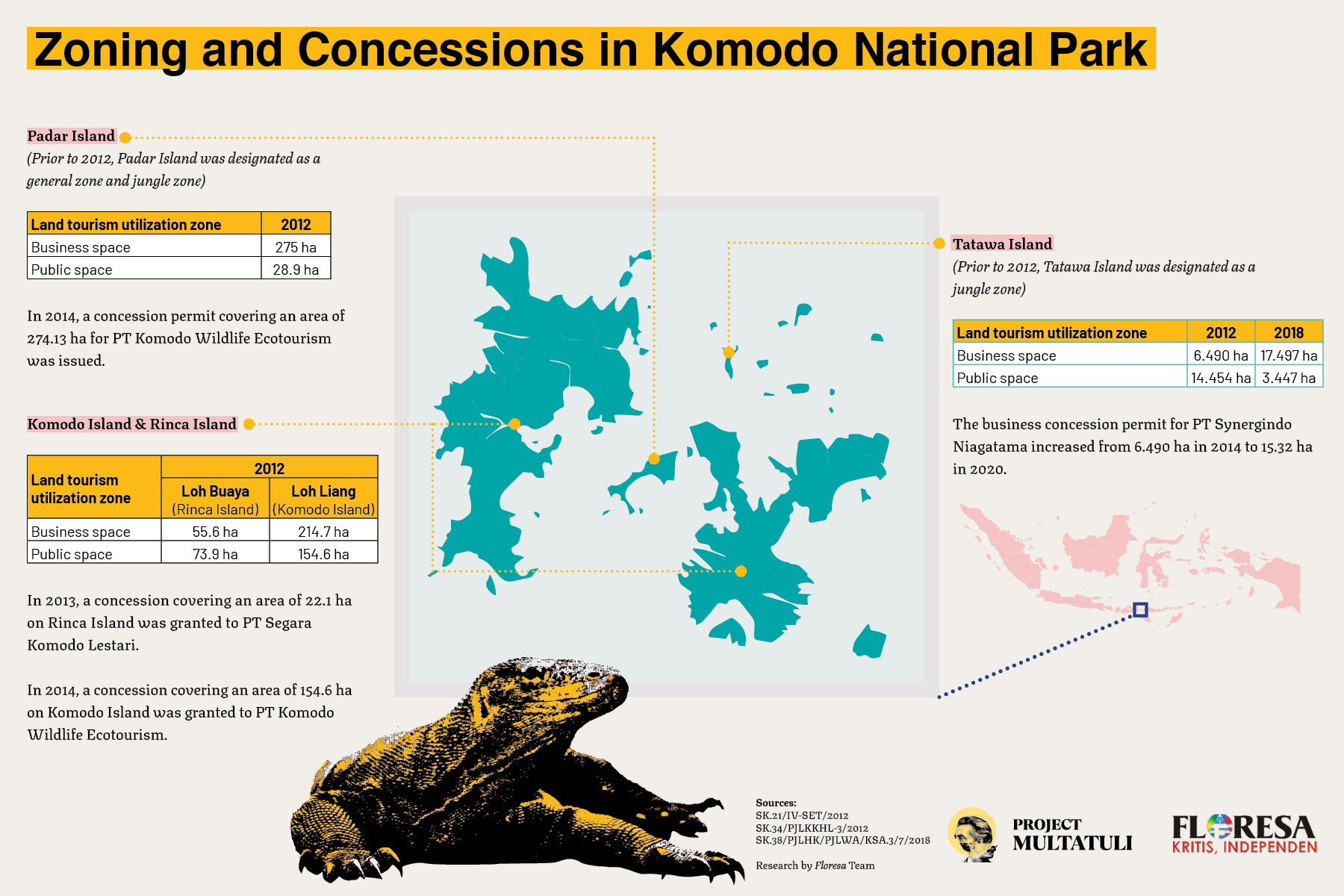

In 2012, a ministerial decree changed the zoning of hundreds of hectares of land on several local islands. Tatawa Island, Padar Island, Rinca Island and Komodo Island became “land tourism utilization zones”.

This enabled the issuance of land use permits for private corporations.

Then, in 2014, the government awarded PT Synergindo Niagatama the use of 6.49 ha on Tatawa Island. The concession was expanded to 15.32 ha in 2018.

In the same year, on Padar Island, it granted a concession of 274.13 ha to PT Komodo Wildlife Ecotourism. The company also received 154.6 ha on Komodo Island.

The government also gave a concession of 22.1 ha on Rinca Island to PT Segara Komodo Lestari in 2013.

According to company documents and reports by Betahita.id and Tempo, these corporations are owned in large part by politicians and hospitality entrepreneurs with connections to palm oil tycoons. They are believed to have a close relationship with President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

PT Synergindo Niagatama, a subsidiary of PT Synergy Tharada, which manages Batam Center International Port, is owned by Mochamad Sonny Inayatkhan. Inayatkhan also serves as finance director of PT Bali Star Resort Indah, which is linked to businessman Kuok Khong Hong, founder of Wilmar International, and Rosa Taniasuri Ong, the wife of Martua Sitorus, Kuok’s business partner.

Rheza Herwindo is the president commissioner of PT Komodo Wildlife Ecotourism. He is the son of Setya Novanto, a former chair of the Golkar Party who was sentenced to 15 years in prison in 2018 for the embezzlement of funds for the state’s digital ID program. He also represented the constituency of NTT for almost 20 years.

PT Segara Komodo Lestari is owned by David Makes, who, with his brother Yozua Makes, founded Plataran Indonesia, a hospitality business partnered with businessman Rosano Barack. Yozua also owns a pinisi sailboat in Labuan Bajo that President Jokowi once rode on.

These businesses’ investments in the area increased during the Jokowi administration, in part to realize the President’s ambition of developing Komodo National Park and its surroundings as a national strategic tourism area.

Not Tourist-Friendly

After East Nusa Tenggara Governor Viktor Bungtilu Laiskodat invited PT Flobamor onboard, the company made new rules limiting tourist access to Komodo Island and Padar Island. They also established a one-year tourist “membership” system for the price of Rp 3.75 million per person.

Tourists visiting these two islands have to buy tickets through INISA, a digital platform launched in July 2022 that provides various public services. Supported by the NTT provincial government and NTT Bank, INISA aims to become a “super application”.

Ismail, the secretary of Komodo village, said a source from PT Flobamor said it was possible that souvenir sellers in Loh Liang would be relocated.

“But hopefully, it won’t happen,” Ismail added. “Because [if they are relocated], I can’t imagine how the people of Komodo will live.”

PT Flobamor’s membership fee was suspended after tourism operators responded with protests and strikes in August 2022. However, the NTT administration has said it will set a new rate at the beginning of 2023.

The Fate of Local Vendors

The many regulatory changes to Komodo island have affected local residents significantly.

Tasrif, who has been working as a naturalist guide for years, is afraid the recent spate of regulations will put locals out of their jobs.

“Even foreign tourists complain about this,” said the 49-year-old. “Every day, they ask, ‘When will the rate increase? And why?’ When the news about the new rate was first announced, we had almost no tourists.”

Adi, a souvenir seller in Loh Liang, said that the government’s plan to designate Komodo Island for middle-upper-class tourists would take income away from small businesses in the area.

“Not all tourists buy souvenirs. In general, only a quarter of tourists make purchases,” he said.

“It’s usually tourists from the middle to lower economic class who shop for souvenirs. Those who come with cruises are rich people. They rarely buy souvenirs,” he added.

He is also worried about the possible relocation of souvenir sellers to Loh Buaya on Rinca Island.

“If we move to Rinca Island, we will only increase competition and conflicts [with the locals there] because we will fight over buyers,” Adi said. “We also need to cover the transportation costs. So we’ll stay in Loh Liang, our ancestor’s land.”

Nur Cahya said she was afraid of losing her income if she was relocated to Loh Buaya. Currently, she was able to earn some Rp 300,000 per day selling food. It was enough to cover her expenses and those of her four children, one of whom is studying in Jakarta.

Nur had once lost her source of income when she was evicted from Loh Liang. She said she would refuse to go through it again.

Kinan, 28, said the corporations in control of tourism areas on Komodo Island often “treat us ruthlessly”.

“This village is ours. The assets here belong to us. Why [is the island] organized by outsiders?” he wondered.

Conservation for Whom?

While private investment flourishes, the government has largely ignored the demands of native Komodo people with regard to their land and fishing areas.

In 2019, Governor Laiskodat announced a plan to relocate Komodo’s residents. The NasDem Party member claimed that as the island served as a conservation region, it should only be inhabited by Komodo dragons.

“The name is Komodo Island, so we need to make sure that the island is only home to the Komodo [dragons]. No humans allowed,” said Laiskodat, who is seeking to move the people of Komodo village to Rinca Island or Padar Island.

Laiskodat’s statement received major backlash from the local people. In July 2022, residents picketed the entrance to the Loh Liang administrative office as government representatives were arriving to discuss the relocation plan. So far, the local people have managed to keep the relocation at bay.

Iskandar, a 54-year-old souvenir seller in Loh Liang, said Governor Laiskodat’s statement made no sense and was “hurtful” to the native people of Komodo. He said the people of Komodo would always protect the Komodo dragons because “they are our family”.

The Komodo people’s special relationship with the island’s dragons extends even to the hatchlings. Komodo dragon hatchlings will hide from the adults, including from their own mothers, who often attack them. Some juveniles seek refuge in the woods, and some seek safety in the homes of local people.

In the course of reporting for this story, on the afternoon of Sept. 9, 2022, we heard a loud cry coming from the roof of one of the houses in Komodo village. Nurlaila, one of the residents, recognized the sound.

“It’s a baby Komodo,” she said, pointing to a dragon the size of a man’s arm on the rooftop.

The juveniles often entered local people’s homes, she noted. “This is usual for us.”

Kinan said the local people had been living on the island for years before the establishment of the Komodo National Park Office and that their traditions ensured harmony with the natural environment.

He said corporations like PT Flobamor wanted to “suddenly reap the rewards”.

“The government came [to us] and spoke with high language. They call it conservation. Conservation is what we have been doing since our ancestors lived here, humans living side by side with Komodo dragons in harmony to protect each other. That is how the people of Komodo conserve Komodo dragons,” he said.

Tasrif questioned whether PT Flobamor would actually aid conservation or empower locals.

“If it’s for conservation, isn’t that the Komodo National Park Office’s [job]? If it’s for empowerment, then what kind of empowerment model do they plan to implement?” he asked.

Omansyah, who has clung fast to his fishing occupation despite the challenges, expressed his frustration at the threat of losing his source of income.

“The Komodo National Park Office already limits our activities. If they take over more locations, we are doomed,” he said.

“I know how corporations work. Several corporations are controlling Komodo now. To put it bluntly, we are strangled,” said Omansyah.

This report is a collaboration between Floresa.co and Project Multatuli. The Floresa team made a report highlighting the voices of the local people who had been impacted by the premium tourism project in Komodo Island and its surroundings. Project Multatuli explored the business interests in the area and who was gaining from the sweeping changes to the islands.

The English version of this story is translated by Project Multatuli