Floresa.co – Only one basket of rice left in a kitchen separate from the main house. No one is yet able to pick coffee, the homeowner’s family’s source of income.

They have little savings left and rice becomes a luxury they cannot afford.

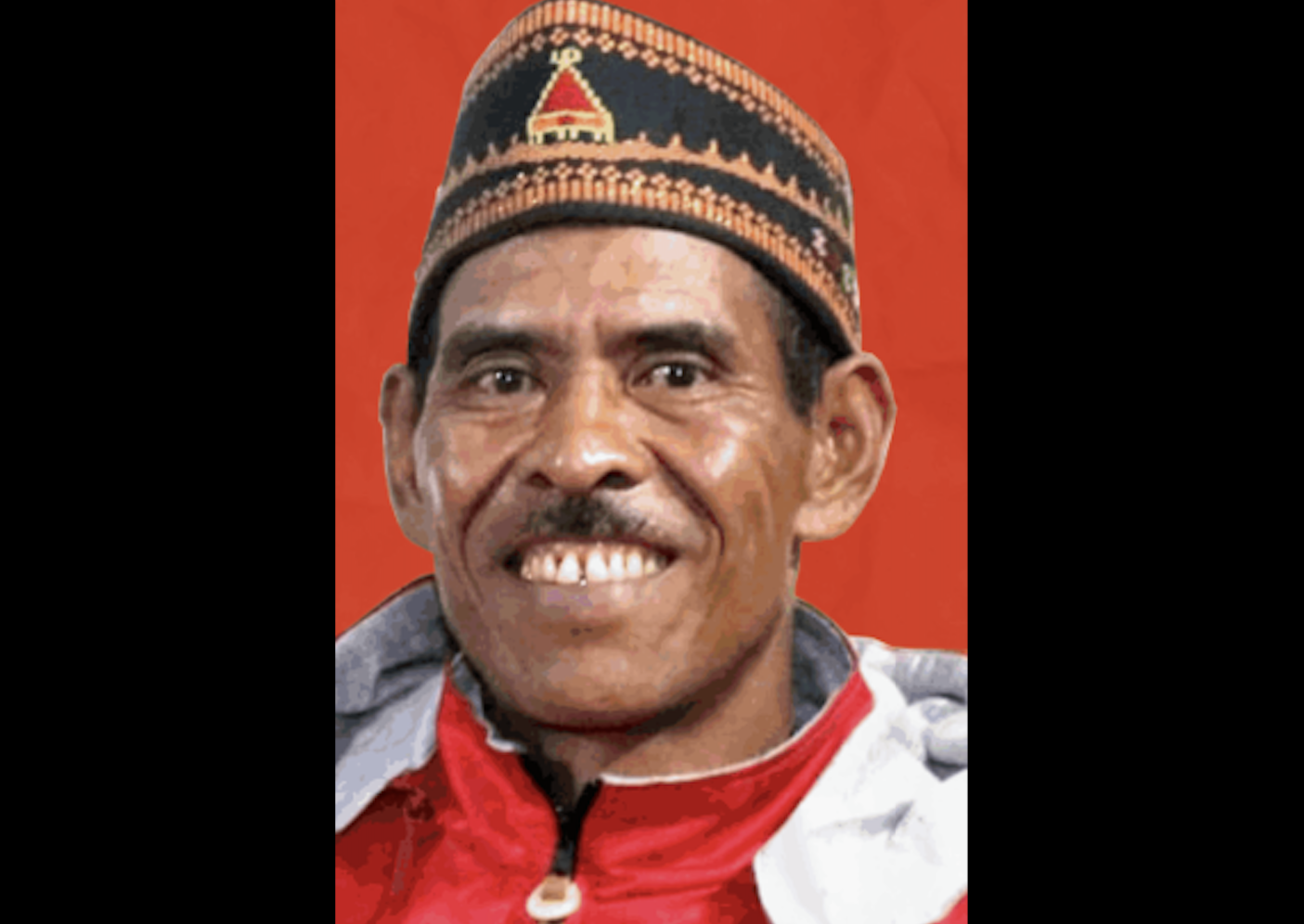

Mikael Ane, the head of the family, has been imprisoned since his arrest on March 28 2023.

Yosep Lensi [28], Mikael’s youngest child, cannot take care of his family’s coffee plantation in Ngkiong Dora Village in East Lamba Leda, East Manggarai Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province.

The family’s inherited coffee farm is located on the hillside of a tropical rainforest. It takes about an hour to walk from their house to the coffee land.

Yosep and his wife, Hildagardis Urni Danse [34] tend their coffee fields for up to six hours per day.

When the two of them worked on the coffee plantations, Yosep’s mother helped look after their eldest child, who was three years old. The youngest was taken to the plantation because he was still breastfeeding.

For six months since March 2023, Yosep has been swamped between taking care of his father, mother who “started to lose enthusiasm for life”, his wife and their two toddler children.

Twice-imprisoned

The tap of the judge’s gavel in early September marked the second verdict for Mikael, a member of the Ngkiong Dora traditional community. He was sentenced to 1.6 years in prison and was obliged to pay a fine of Rp300 million.

In the September 5 decision, the judge found Mikael guilty of building a house in a location that the government claimed was included in the Ruteng Nature Tourism Park [TWA].

Ten years ago, he received a sentence of 1.2 years in prison for cutting down woody trees in an area designated by the government as covered by the Ruteng TWA.

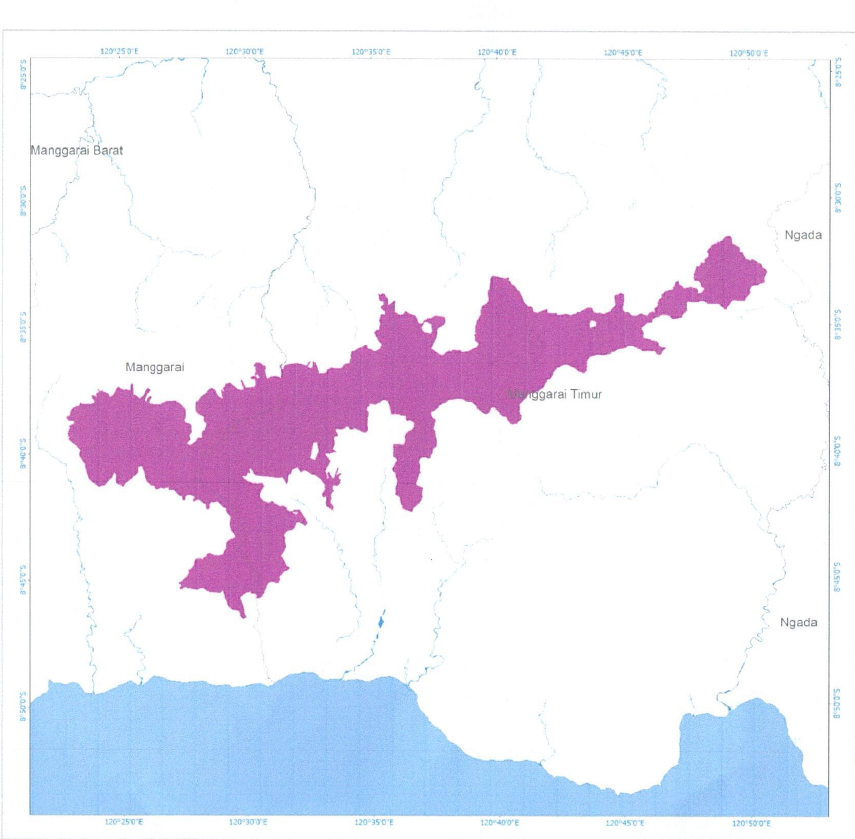

The conservation area covering 32,245.6 hectares extends to 57 villages in nine sub-districts covered in the administrative area of two districts, Manggarai and East Manggarai respectively, which are located on the west side of Flores Island.

In East Manggarai, the Ruteng TWA area includes Lembah Colol and Ngkiong Dora. Both are the main coffee centers in the district.

Yosep said that 10 years ago his father cut down a number of woody trees to open up new land for his coffee saplings. He “had to do it because the coffee plants on his previous land were getting old.”

Even though he doesn’t understand the average age of coffee plants on his previous land, Yosep remembers one day Mikael said: “These plants have been growing since your grandparents’ time.”

Moreover, added Yosep, “my father cut down the timber [trees] outside the boundaries of the conservation forest. It shouldn’t be a problem.”

Customary Lands

Ngkiong Dora is 8.7 kilometers from Colol Valley. Both are connected by a section of district road which is damaged here and there, making a trip that normally takes 10 minutes take 20 minutes.

Like the traditional communities of Greater Manggarai in general – including West Manggarai, Manggarai and East Manggarai, the Colol and Ngkiong Dora residents also have a land distribution system called lingko.

Lingko is determined using three mechanisms, namely lodok, neol and tobok. In short, the determination using these three methods ultimately forms a kind of spider web with triangle-like slices. This slice shows the land resulting from customary division.

The Colol indigenous community has 64 lingkos with an estimated area of around 1,270 hectares, according to Book 3 – National Inquiry of the National Human Rights Commission [Komnas HAM]: Agrarian Conflicts of Indigenous Peoples over Their Territory in Forest Areas.

There is no definite data regarding the number of lingkos in Ngkiong Dora. What is clear is that traditional elders who deal with customary land issues [tua teno] always lead traditional deliberations first in order to “arrange the distribution of land fairly and wisely.”

The Customary Area Registration Agency [BRWA] noted that the government established the boundaries of the Ruteng TWA on October 28, 1998. The boundaries “narrowed the plantation land of indigenous people” and triggered a series of events involving the government and indigenous communities.

BRWA recorded 25 incidents of burning huts, uprooting coffee saplings in farmers’ plantations and criminalizing Ngkiong Dora residents during 2012-2016.

The incident included the uprooting of Mikael’s 525 coffee seedlings, the confiscation of goods and Rp28.5 million from his family’s hut and his prison sentence.

Troubled Boundaries

The Ruteng TWA conservation area has been involved in boundary disputes for not only a year, but two years.

It all started in 1936, or when the conservation area was still called the Ruteng Forest Group.

At that time Indonesia was not yet independent. Timor Resident Onder Horiloheyden designated the Ruteng Forest Group as forest cover—a forest zone dominated by tree vegetation typical of tropical rainforests, for example orchids and woody trees.

Apart from being rich in vegetative structures, the forest, which is at an altitude of 500-2,350 meters above sea level, is also home to 65 species from 35 bird families.

Elisa Iswandono, a researcher on indigenous communities, food security and tenure security at the Bogor Agricultural Institute, found that 69 types of plants in the Ruteng TWA were used as medicinal plants. For example loi [Alstonia spectabilis], tambar [Tinospora crispa] and tepotai [Geniostoma rupestre].

In order to maintain biodiversity in the Ruteng Forest Group, the Dutch East Indies government created a border.

The boundaries in the form of stacked munggur stones are arranged at such a distance so that, among other things, planters around the Ruteng Forest Group could clearly know the planting boundaries without violating them.

Because it is only a structure of stone, the boundaries gradually blur.

“Perhaps there are people who don’t understand that [the stone arrangement] is a border marker, so they move it,” said Jon Fransiskus Basiru (62) in front of his yard in Lembah Colol, East Lamba Leda, East Manggarai Regency.

Jon is a traditional elder of the Colol Valley. He identifies himself as part of the Maro traditional community, which has cultural roots in Gowa, South Sulawesi.

Jon remembers that representatives of the NTT Center for Conservation and Natural Resources [BBKSDA] came several times to the Ruteng TWA boundary on the side closest to his village.

According to Jon, their arrival at that time was to “remeasure the boundaries because the boundaries of the Dutch heritage were no longer clear.” In 1980, said Jon, “The NTT BKKSDA came here to replace the stone structure with hanjuang.”

Andong or hanjuang [Cordyline fruticosa] is a plant with minimal stems or even no branches. Such stems often make hanjuang a barrier between gardens on slope contours with oblique paths.

In 1993, the government changed the name and function of the Ruteng Forest Group to TWA Ruteng.

This years-old agrarian conflict passed its worst period on March 10 2004, or in an event known as “Bloody Wednesday”.

“Fatal Approach”

That Wednesday, first coffee farmers around Lembah Colol, East Lamba Leda, East Manggarai visited the Manggarai Resort Police [Polres] in Ruteng, the district capital.

Their arrival at the Polres was to demand the release of seven Colol Valley farmers. Arrested the day before, they were thought to have encroached on state forest areas.

Four of them were women.

Apart from arresting farmers, the police also cut down coffee stalks and demolished farmers’ rest huts in the Ruteng TWA area.

On Wednesday towards the end of the first quarter, a demonstration in front of the Manggarai Police Station ended in chaos. The trigger is confusing, but what is clear is that at that time the police opened fire on the farmer demonstrators.

Six farmers died and 28 others were injured. Of the nearly 30 injured victims, three of them were disabled for life.

The National Human Rights Commission [Komnas HAM] in its report stated that the Manggarai Regency government and Manggarai Police had committed human rights violations, especially civil rights, in the shooting case on March 10 and the arrests the day before.

The report, as cited in the book Gugat! Blood of Manggarai Coffee Farmers, stated that the arrest of the seven residents was not accompanied by a warrant. Apart from that, there are strong indications that the police do not give residents the right to be accompanied by a lawyer during the investigation process.

Not only that, one suspect was a minor. The suspects were also not informed of the reasons for the arrest and the alleged crimes, as well as the alleged verbal abuse.

Wiratno, former Head of East Nusa Tenggara’s Center for Conservation and Natural Resources [BBKSDA NTT] in 2012-2013, knew about the events of those two days.

“The government knows there is a problem in the Colol Valley,” he said on the other end of the phone, “but has instead insisted on an approach that is clearly wrong and has fatal consequences.”

Two Ways Out

Not long after being appointed as Head of BBKSDA NTT, in 2012 Wiratno visited Colol Valley. “I came as a traditional sign of mourning for the death of the Colol farmer on ‘Bloody Wednesday,’” he said.

He admitted that his arrival “was not based on an invitation from Colol residents, but I was the one who wanted to come there.”

A few days before leaving for Colol from Kupang, the capital of NTT, he first contacted the Colol traditional elders to ask for permission to visit.

Wiratno at the same time called his arrival in Colol “my apology as the Head of BBKSDA [at that time].”

The traditional ceremony was held at the Colol rectory, witnessed by representatives of the indigenous community, BBKSDA NTT and the local parish priest.

After the mourning ceremony, Wiratno and representatives of the local church surveyed the latest boundaries several times which were adjusted to the conservation map. The result, said Wiratno, “is the true boundary of Dutch heritage.”

In December 2012, the “Three Pillars” concept was born which, at that time, was believed to be the best way to resolve the Ruteng TWA boundary dispute.

“Three Pillars” is the result of a series of traditional deliberations [lonto leok] between indigenous communities, BBKSDA representatives and representatives of the Catholic church.

Apart from Wiratno, the document formulating the “Three Pillars” concept was also signed by representatives of indigenous communities, media representatives, representatives of non-governmental organizations, the then Bishop of Ruteng, Hubertus Leteng and the then Regent of Manggarai, Christian Rotok.

This document essentially formulates two solutions to the long-standing dispute in the Colol Valley.

First, the government and Colol’s indigenous peoples need to agree on a special block on residents’ plantation land which overlaps with the Ruteng TWA. The block will later be determined by the Director General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation at the suggestion of BBKDA NTT.

This process was predicted to take a year starting in January 2013 or a month after the signing of the “Three Pillars” document.

In reality, the determination of the special block has not been implemented to this day.

Second, all lingkos that have been taken over and turned into forest areas by the Dutch colonialists and continued by the Indonesian government should be removed from the map of the Ruteng TWA area.

The document stipulated that they should be returned to the Colol indigenous community. There is still no clarity regarding that matter.

Less than two years after visiting Colol, Wiratno was appointed as Director of Social Forestry at the Ministry of Environment and Forestry [KLHK]. Wiratno is currently the Director General of Conservation and Natural Resources at the Ministry of Environment and Forestry.

He admitted that he still frequently communicates with Yoseph Danur, a traditional leader of the Colol Valley. Yosep also signed the “Three Pillars” document.

With Floresa, Wiratno also shared several photos of Yoseph. Under one photo sent via the WhatsApp chat application, he typed, “Yoseph Danur, my good friend.”

Meanwhile, in the Ruteng TWA boundary, the “Three Pillars” has not been implemented.

Indigenous communities and the government continue to have disagreements regarding boundaries.

Coffee farmers are starting to worry that at any time they will lose their inherited land. Losing land also means losing income.

Constitutional Recognition

While the “Three Pillars” concept has not been implemented, the existence of indigenous communities around the Ruteng TWA has not been legally recognized by the state.

The Inquiry Commissioner Team stated “the development process with an emphasis on infrastructure development and management of natural resources as well as environmental preservation requires certainty of control rights over land and other natural resources.”

The lack of certainty “will complicate the issue of overlapping land rights of customary law communities,” said Sandrayati Moniaga, former Komnas HAM Commissioner and Coordinator of the National Inquiry Commissioner for Komnas HAM.

At the same time, the state as the main holder of the obligation to respect, protect and fulfill human rights “must also strive to recognize the existence of customary law communities.”

The lack of recognition of indigenous peoples is also a concern for Ermelina Singereta, Litigation Manager of the Association of Defenders of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago [PPMAN].

PPMAN is a legal assistance service for indigenous communities provided by the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago [AMAN].

Ermelina Singereta is one of Mikael Ane’s three attorneys. Accompanying Mikael during the trial, Ermelina stated that “the lack of recognition of indigenous peoples makes them vulnerable to imprisonment.”

Based on this concern, PPMAN registered a lawsuit against President Joko Widodo and the People’s Representative Council. The lawsuit was registered with the State Administrative Court [PTUN] on October 25 2023.

There are 10 applicants in the lawsuit, namely a representative of the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago [AMAN] and nine representatives of indigenous communities from several regions of Indonesia.

As many as 7 of the 9 representatives of indigenous communities are currently in prison, including Mikael.

Meanwhile, seven Colol coffee farmers who were arrested in Bloody Wednesday were finally released, seven days after their arrest.

The lawsuit was filed because “the Indigenous Peoples Bill which has been in process since 2009 until now has no certainty,” said Ermelina.

The Indigenous and Legal Communities Bill has been included in the DPR’s Priority National Legislation Program [Prolegnas Prioritas] list for 2022. However, the bill has not yet advanced to level II or plenary.

The agreement of DPR members to bring a bill to the plenary level indicates the discussion stage with the government which can result in its ratification as law.

Since the Community Bill was never passed, said Ermelina, “indigenous communities are threatened with losing their expressions, habits, ideas, origins and even identity.”

Indigenous peoples, she said, “are not statistics. They always respect nature and life itself.”

For indigenous peoples, “life is about struggle and survival. The country has to fight for them.”

In front of his house on a hot afternoon typical of the East Nusa Tenggara climate, Yosep Lensi carried buckets of water back and forth from a pipe supplied by the local government.

Pausing for a moment to catch his breath, he looked at the slope of the forest that surrounded his family’s house.

“Our coffee plantation is deep in the forest on that slope,” he said before continuing, “we have to continue to look after it.”

Editor: Ryan Dagur

This is the second part of two reports on Colol coffee farmers, which coverage supported by the Earth Journalism Network. The first report can be read here.

The English version is translated by Anastasia Ika. Read the original story in Indonesia language here